Caine: Then why bother?

John: Maybe I am wrong.

John Wick 4, (2023)

It’s been a long overdue to write a post about my past year’s Google Summer of Code (GSoC) project. jnigen is an experimental bindings generator which aims to provide Java interoperability for Dart. It works by generating wrappers which call JNI through Dart’s FFI (Foreign Function Interface).

I developed the initial versions of this package under the guidance of Daco Harkes and Liam Appelbe from Dart team. Hossein Yousefi from Dart team is developing the project further, adding many features such as Generics and Kotlin language support.

Why?

The current way of accessing platform APIs on Flutter is Method Channels. Channels neatly avoid the intricacies of native language interop, by using an message passing mechanism instead. However, there are a few drawbacks to this:

All calls to method channels have to be asynchronous

Sharing memory is not possible.

De/serialization of data across the language boundary is relatively expensive.

Perhaps more important, currently the use of method channels requires writing quite a bit of boilerplate. 1

Therefore, it’s desirable to have an automatic bindings generator for Java libraries, for ergonomics reasons. Using FFI instead of method channels enables better performance and eliminates the need for asynchrony as well.

Dart already has an excellent bindings generator for C, called ffigen. It was written 2 years ago by Prerak Mann, in 2020 GSoC. It has been later extended to support Objective-C as well. It uses libclang to parse the C headers and generate wrapper code for calling them. The goal of jnigen was to provide similar facility for Java libraries, by combining Dart’s FFI and Java Native Interface (JNI).

We had the prior art of ffigen which simplified several decisions. However there were challenges unique to Java.

- How to parse the Java libraries? In C/C++, libclang is ubiquitous for this purpose.

- In case of C, the

ffilibrary is already provided by the dart. For Java, we had to develop a support library. - C dependency graphs are fairly sparse, and you can provide some header file paths to the tool. In comparison Java build systems and dependency configurations tend to be complex systems in their own right.

As a rule of thumb, everything about Java interop (runtime, parsing, build) is less known, or less obvious. As a student, GSoC was my first attempt to write anything with real world scope. Therefore, I learned several practices and principles.

The aim of this post is to give a glance of various architectural and design decisions, as well as the lessons I learned from this project.

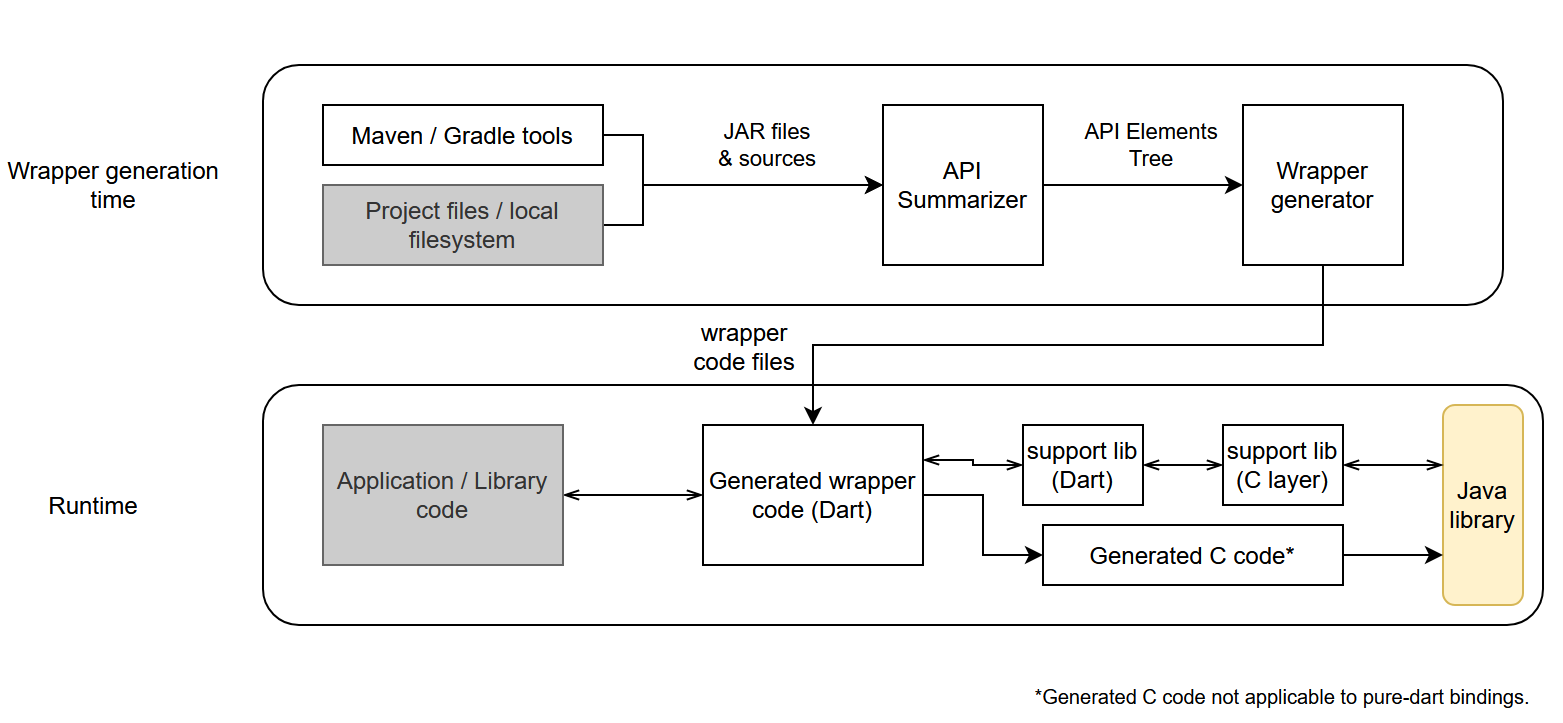

Before we start, here’s a post-facto, approximately-correct architecture diagram which might explain what I am actually trying to build:

JNI runtime support

JNI is an native interface designed with C interop in mind 2. Therefore, a number of quirks have to be considered when our goal is to abstract the JNI to a high level language like Dart.

Differences between platforms

On Android, Flutter application runs embedded in Android JVM. Therefore the VM already exists. We just initialize the JNI using a plugin, and also obtain a reference to application context.

On standalone targets (Flutter Desktop and standalone Dart), there’s no JVM. On initialization, a JVM has to be spawned, using the JRE available on the machine. If you intend to use some external libraries, (like the PDFBox library we use in one of the example), the JAR files must be provided as classpath.

Besides, using jnigen requires support library written in C. It’s packaged automatically with Flutter apps since it’s a native plugin. However, this library’s path must be provided with standalone.

99% of real world application of Java interop will be on Android. There are enough quirks in standalone support 3 that they outnumber the population of some European countries.

Then why take the pain to implement support for standalone targets? Having standalone support enables unit testing of support library & generated bindings. This feedback loop is invaluable.

Thread-local this, thread-local that

JNIEnv struct, basically a vtable of 200+ functions, provides the entry point for most functionality of the JNI. Unfortunately this struct is valid only in the thread it is obtained.

Dart being a high level language, Thread pinning is not yet supported, and we didn’t want to rely on implementation details of threading, in presence of async-await in the language. Thus the JNIEnv * was wrapped in a thread_local. This singleton design was not really a problem, because there can be at most 1 JVM in a process, anyway.

For the same reason, all references returned from JNI are converted to global references before returning to Dart. This works fine in practice. Reference lifecycle is handled by NativeFinalizer mechanism, with an API for explicit deletion if required.

The curious case of the UI thread classloader

Android has a concept of UI thread. Confusingly, in a Flutter app, this is different from the thread running Flutter application.

It turns out, most platform classes are not available if you call JNI’s FindClass from a flutter thread. This is because those threads have a much barebones classloader. The solution suggested by Android Developers documentation is to store a reference to original thread’s class loader and call its loadClass method instead of JNI’s FindClass, which worked for us.

The perils of dynamic loading

The generated C code needs to call the function in C support library. At minimum, it should be able to access the shared context such as the class loader. However, we can’t link them in compile time, with existing Flutter build system.

The other solution is to load the DLLs into a shared namespace. However it was not feasible because on some platforms, DynamicLibrary.open implementation loads symbols into local namespaces of the library, and not expose it. 4. We worked around it by having the initialization code in dart, which set some pointers in generated C code. 5

After all the workarounds, it was possible to use JNI from the support library package:jni. Although it wasn’t most ergonomic thing to use directly, it was supposed to provide a layer shared by all generated wrappers.

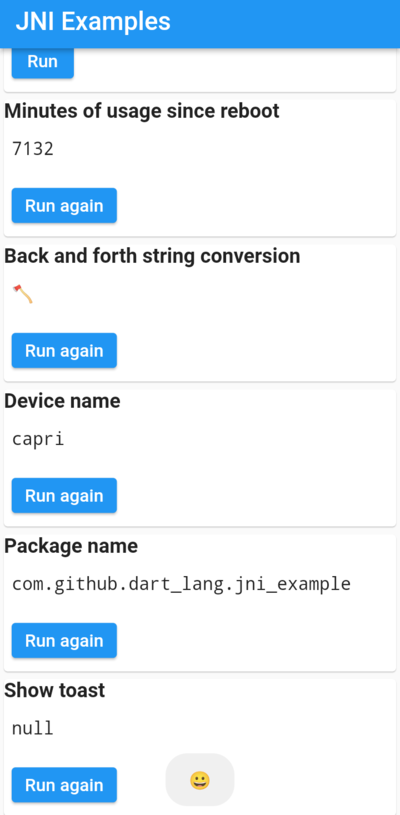

A glimpse of one-off APIs

My litmus test at these stages was being able to call some Android built-in APIs, such as displaying a Toast message, or getting time since boot 6. The latter will be a simple one-liner on Android.

long millisecondsSinceBoot = SystemClock.uptimeMillis();

If you call this using JNI primitives, there will be a number of steps

- Find class

SystemClock. - Find static method

uptimeMillisonSystemClock. A fairly cryptic signature also needs to be specified. Here the signature is()Jwhich means this method takes no arguments and returns along. - Call this static method and obtain the result.

- Check if there’s an exception.

- Return the result to the caller.

While the ideal way to avoid this is generating wrapper, support library package:jni still provides a way to call methods without generating code. This layer of abstraction is intended for one-off usages and testing. It’s still quite verbose but better than calling the methods on JNIEnv directly.

Jni.findJClass("android/os/SystemClock").use(

(systemClock) => systemClock.callStaticMethodByName<int>(

"uptimeMillis", "()J", [], JniCallType.longType),

);

These are “stringy” APIs which are only supposed to be for one-off uses where you can’t generate code, and debugging. The actual jnigen-generated bindings will use slightly lower level APIs, storing method references etc.. into class fields when appropriate.

Parsing Java libraries

The problem: we need an AST

To generate bindings, we need to know the API of the library. If we consider a method, we need to know the name of the method, types of arguments and return types. We will also want names of arguments, and ideally the documentation comments to be carried to the target language. Similarly, we need to know what classes and fields are there, what’s the superclass of given class, etc.. All of this information will be in hierarchical manner. Sounds familiar right? We need this information as an Abstract Syntax Tree.

This tree does not need to contain the information down to statement or expression level. However, AST is the closest term to what is required here. This hierarchical API information has to be parsed from some artifact, which is either JAR file, source code or JavaDoc HTML.

(Modern IDEs do a lot of similar things. For example, IntelliJ IDEA displays the documentation on hover, if you configure it to download JavaDocs or sources.)

parsing JARs vs parsing the source

I first tried parsing the JAR files using the excellent asm library. But soon I stumbled upon the caveat, that compiled JARs do not contain parameter names for methods. 7

So I went ahead and created a prototype using javaparser library, which can parse the source files, and has a workable symbol resolver. However, later we decided in favor of OpenJDKs doclet API, which has the benefit of being on par with the standard OpenJDK compilers. While the default doclet produces API documentation in HTML format, we can use the API to produce a JSON of API exported by the library, which represents the hierarchical tree structure.

One drawback of doclet parser is that it requires the Java source code to be well formed. That is, if you have a source file referencing a class Xyz, this Xyz class has to exist somewhere in sources or classpath you provided to this tool. This implies that all compile time dependencies of the class has to be present. It’s a significant limitation. There’s a plan to support a more tolerant source parser, using QDox / JavaParser / Eclipse ECJ, which will eliminate the requirement of having all dependencies.

Later, we also added support for parsing JARs using asm. Because it’s convenient for cases where we cannot get well-formed sources. Also, Kotlin support which was added later works using this parser.8

Why output JSON and not use JNI?

This parser component (called ApiSummarizer) currently runs as a standalone process and outputs JSON. You might ask “why does it not use JNI itself”? To be honest, we just haven’t got time to do the dogfooding exercise.

Besides, such an implementation will be fairly verbose with the features currently supported by jnigen, since the communication from ApiSummarizer is an one way street with a single JSON blob of “plain old data” type. When jnigen matures, it might support the plain-old-data types better which will also reduce the effort of such dogfooding.

Generating code

Unlike what we expected in the beginning of the project, a significant portion of effort has gone to the support library and parsing, and less to the generated code. Code generation is basically templated string concatenation. The generated code contains functions which call the corresponding C function.

The initial plan was to have each Java symbol generate a wrapper function in C, and have the Dart wrapper call this C wrapper. In the hindsight, this C function should not even be required because we can factor most calling patterns into few Dart functions, and factor them into the support library’s dart interface. I wish this was the path I followed from the beginning. Currently we have both versions of bindings (Pure dart and Dart+C). They’re both tested with same test cases.

The long-term plan is to do some benchmarking and discard C-based bindings. Pure dart bindings have the advantage of not complicating the build system. They can be just built as normal flutter package without any native dependency except the JNI support library. Further, it’s only dart code and lends to tree shaking, unlike the C bindings which have to be built as shared library.

The only disadvantage at the time of implementation was the unavailability of FFI varargs, requiring a native allocation for each call to pass the arguments as an array. Now that FFI varargs are available in Dart, I expect this gap to reduce soon.

For sake of completeness, here’s what our SystemClock.uptimeMillis binding looks like in generated code.

static final _id_uptimeMillis = jni.Jni.accessors

.getStaticMethodIDOf(_class.reference, r"uptimeMillis", r"()J");

/// from: static public native long uptimeMillis()

static int uptimeMillis() {

return jni.Jni.accessors.callStaticMethodWithArgs(

_class.reference, _id_uptimeMillis, jni.JniCallType.longType, []).long;

}

As you can guess, it can be called as easily as in java - SystemClock.uptimeMillis().

Not all calls will be this easy though. Sometimes there will be more boilerplate involved. All Java classes are wrapped as subclass of JObject type, which wraps a JNI global reference. This applies to Java String as well, which gets mapped to JString class in Dart. Therefore, passing Strings to Java methods requires calling .toJString extension method.

Sometimes it’s not possible to generate bindings for a required class, it can be still accessed through reflective APIs. This is a snippet from the examples in jnigen repo.

final inputFile = Jni.newInstance(

"java/io/FileInputStream", "(Ljava/lang/String;)V", [file]);

final pdDoc = PDDocument.load6(inputFile);

int pages = pdDoc.getNumberOfPages();

final info = pdDoc.getDocumentInformation();

final title = info.getTitle();

final subject = info.getSubject();

final author = info.getAuthor();

stderr.writeln('Number of pages: $pages');

if (!title.isNull) {

stderr.writeln('Title: ${title.toDartString()}');

}

In this, we couldn’t generate bindings for FileInputStream class9. But it’s still possible to use a FileInputStream with the escape-hatch.

Package manager integrations

As previously mentioned, the source code needs to be well formed for parsing. Most Java code in real world, especially Android code, will have bunch of dependencies which are difficult to procure manually. It’s desirable to have a way to get these dependencies from maven or gradle.

Maven has an excellent plugin called Maven dependency plugin which simplifies most of work with maven dependencies. There’s some thin code wrapping over this command. It makes getting libraries like pdfbox (which we used in a standalone example) a breeze. You can specify something like this in jnigen.yaml and jnigen will download the JAR / sources from maven. 10

maven_downloads:

## For these dependencies, both source and JARs are downloaded.

source_deps:

- 'org.apache.pdfbox:pdfbox:2.0.26'

## Runtime dependencies for which bindings aren't generated directly.

## Only JARs are downloaded.

jar_only_deps:

- 'org.bouncycastle:bcmail-jdk15on:1.70'

- 'org.bouncycastle:bcprov-jdk15on:1.70'

Similarly, we have a use case of generating bindings to Java files in an Android app project (as opposed to a generic library). These depend on various Platform and AndroidX libraries which cannot be obtained by maven. We currently workaround by running some gradle stubs which print the paths to these JARs on local system. Long term plan is to migrate this logic to a gradle plugin.

Configuration

My initial plan was to expose jnigen as an API, so that users can write a dart script in tool/ directory of the project and call it. However, Daco suggested to provide a YAML configuration similar to what ffigen does. It was indeed a better idea from end-user perspective. (At least, this project is not kubernetes-scale and will never require templated YAML packed in an OCI container image).

Another nice effect of implementing YAML config is that it steered the design of configuration towards being more declarative and tidy. In my initial design, user would’ve to imperatively call the maven utilities described above, using an API. Later, I just made it another configuration parameter, which is much nicer.

Other stuff

Code generation is heavily used even inside the project. One set of tests which test Dart+C bindings are replicated to test pure dart bindings. This can’t be abstracted in code because imports will be different, so code generation is the practical option here. Similarly, a script written against ffigen’s internal AST representation is used to generate some C wrappers from jni.h of Android NDK.

CheckJNI on Android has been quite helpful. In the beginning, some functionality was only tested on standalone using unit tests. We wanted to run same unit tests on Android. Since there’s no provision in flutter for running Unit tests on another device, we made a stub application which ran these tests using integration test mechanism. This uncovered bugs which didn’t occur on standalone target. For instance the spec defines NewGlobalRef can’t be called when an exception is pending. However it happened to work on standalone Dart target (which uses OpenJDK using the JNI invocation API), and the bug was found when the same test was run on Android.

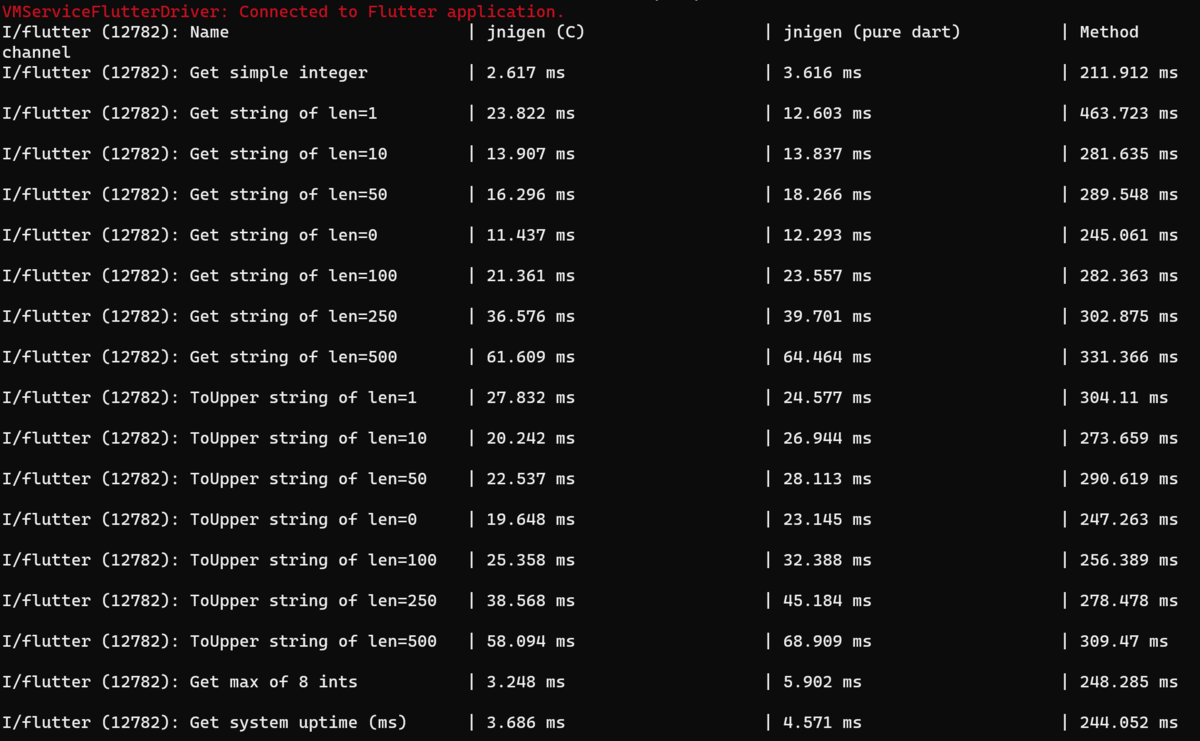

Performance on small tests seems good so far. On a synthetic benchmark which mainly measured trivial calls, we can see more than 10x average improvement over method channels. In practice, if you call into Java, Java code needs to justify it by doing some heavy-lifting anyway. So I believe the main value of the code-generation interop is ergonomics, and then performance.

Future work

I have to admit that I underestimated the complexity of this project. It’s usable in current state (at the time of writing this), but there’s lot of work to be done. Having almost no prior experience with real world programming, I am perplexed at the architectural detail it took to get the smallest things working.

After last December, I became busy with other stuff including college work, and only contributed to the project intermittently. During this time, Hossein from Dart team took up the project. He has developed some amazing features such as Generics, special support for common types (List, Set), and Kotlin support (including suspend functions).

Language features

Callbacks into Dart is the most obvious missing feature. It’s not straightforward to do this generically with JNI. The current plan is to use Proxy classes.

Generics, exceptions and inheritance implementations are very barebones, and need to support more Java features. For example, all exceptions in Java are thrown as JniException, which makes it difficult to handle different exceptions in catch clauses of Dart code.

Kotlin support is another thing. Kotlin and Dart are both languages with a chocolate shop of syntactic and type system features, and interop with Kotlin will be more sophisticated than just Java interop.

Obtaining sources and parsing

Gradle integration as it exists today is a hack. It has to write a stub build.gradle file, run it and collect the paths of dependency JARs. The proper way to do it is using gradle plugins.

Requiring well-formed sources is another pain point. We would ideally have another more tolerant parser for partial sources, which would gracefully degrade when a symbol encountered in source is undefined. The plan is to implement such an option using an open source parsing library, or alter one (Starting from a grammar is impractical.)

Performance

Currently, overhead of JNI call appears to be around 10% of the Flutter method channels, from some basic benchmarking. More rigorous benchmarking is needed, of course.

It could be optimized further, but it wouldn’t be a very productive endaveour to microbenchmark extensively - because real world usage patterns vary between platform channels and code-generation based interop.

If you’re calling Java code, it has to be doing some heavy lifting, like calling some system APIs which cost more than the overhead of method call itself.

The difficulty of writing method channel code may force to keep the interface small with very few methods, which will usually have a positive impact on performance.

With channels, you can probably squeeze a little more performance by using

BinaryCodecand writing tight ser/de code.

It’s always (whether using channels or JNI) a good practice to keep the interface between languages small.

The niche performance opportunity with having JNI as interop layer instead of serialization is sharing native memory through DirectByteBuffer. It would be nice to have an API similar to typed_data which facilitates sharing memory.

Better support for “Plain Old Data” types

Some classes are just structured containers for data. The current jnigen translation scheme assumes every class has behavior, and fields are accessed individually. But sometimes, it’s better to treat an object as a container of structured data, and eagerly convert all fields into Dart types.

To give an example, suppose we have a class called name. For brevity, let’s ignore all getter / setter conventions.

class Person {

String firstName;

@Nullable String middleName;

String lastName;

int age;

}

JNIgen will wrap this into a Dart class, containing a reference to original object and accessing String fields through JNI when they are required. Further, any field of non-primitive type (including String), will return a wrapper object referring to a Java object.

But when all of this is a heap of data, and if we never pass anything from this back into Java code, then it’s better to convert the entire structure into a dart class at one go, and discard any references into Java.

// dart

class Person {

String firstName, lastName;

String? middleName;

int age;

// ....

}

The pedantic observant reader would point out that it’s just deserialization in disguise.

It will be certainly interesting to see whether binary-deserializing the entire thing into a byte buffer, and deserializing it back from Dart will be more efficient than populating the target POD structure field-by-field. Either way, the primary value in such conversion is ergonomics (getting a dart POD type without any effort) and not performance minutiae.

Lessons learned

jnigen was my first project with real world scope. I personally learned few valuable things about software engineering in general.

Aggressive Automation

The basic principle of our profession is that computer can do repetitive things much, much better than we can. Whenever there’s a repetitive task, I was adviced to create a script for that rather than documenting the commands for that.

Sometimes it appears automating something is not worth it because initial automation effort exceeds the (apparent) time saved. That sentiment, however, neglects the reproducibility benefit of scripting something.

Something can take 30 second and may appear “not worth scripting” when you have full context of the code. However, the 30 second may become 10 minutes once you lose context, or someone else has to perform the same sequence of 5 commands. I have come to firmly believe reproducibility and knowledge transfer effects of automating things are worth more than the initial time investment in most cases.

Testing

Perhaps due to the disconnect from real world software engineering, most students are never taught how to test, and the importance of correct testing. The main purpose of having automated tests is not finding bugs - it’s about making changes peacefully without the fear of breaking something somewhere. From that perspective, writing automated tests is mostly about velocity more than correctness.

Another lesson was that tests are also code, and thus have to be abstracted properly. In practice I always found myself writing a test_util directory. Often, many tests follow same pattern and we can just vary the parameters. One great thing about Dart’s testing libary compared to JUnit / TestNG etc.. is that a test is registered with single function call, which makes it less awkward to abstract away various patterns than with classes and annotations etc..

I also learned some discipline with testing. Initially I had written too many end-to-end testing, and not many unit tests. As time passed, they took too much time to run.

Well architected is half done

While its impossible to achive a perfect architecture, there are many things in jnigen which, had I architected them better, would’ve saved much time down the line.

I have learned the sense of good design, apart from intuition, requires a broad knowledge - including the understanding of how things are done in various other software.

One small example is the command line option overrides. I implemented the overrides mechanism similar to system properties in various Java applications, (-Dproperty.name=value), with list values being delimited by ;. This would help to change the properties for single invocation of the tool, which has been found quite useful.

If I were to implement it today, I would consider arbitrary JSON overrides rather than splitting by : - which would’ve been more elegant and support more complex values. This realization occurred when I saw the override mechanism in helm.

Another small example: in tests, we generate and compare bindings with a set of reference bindings. Instead of using string comparison, we found its a good idea to invoke git diff --no-index, which gives a better line-by-line diff.

Similarly, keeping logs as files was inspired by CMake and kdesrc-build.

Conclusion

I am optimistic that jnigen will be versatile Java (and Kotlin) interop toolkit for Dart one day. If it doesn’t, we will have enough lessons that might help someone implementing JNI interop for some other language.

Personally, participating in this project has been a skill upgrade for me. It was an architectural and implementation challenge, and I had so much lessons to learn.

I’d like to thank the Dart team members, especially Daco, Liam and Hossein, for their guidance in the project. I’d also thank the GSoC program for giving a chance to me, someone with no other interesting programming background, to get involved.

pigeondoes a bit to alleviate this, but still requires the developer to specify the interface and implement it in platform language. Tools likeffigenandjnigenapproach it from different direction, by binding to whatever interface is exposed by the library. ↩︎currently a newer interface is implemented as part of Project Panama, but it won’t be on Android anytime soon. ↩︎

One of such surprises is that, on Windows, you have to link the JVM libraries using

DELAYLOADlinker flags, or else it fails to load with a generic error code. It reminds me ofNo such file or directoryerror in Linux, which can in fact happen due to a missing library. ↩︎The default behavior appears to differ across platforms. Windows and MacOS use global symbol namespace (

RTLD_GLOBALor equivalent), whereas Android and glibc use per-library namespace (RTLD_LOCAL). TheDynamicLibrary.openin Dart FFI doesn’t have a way to change this, since it’s cross platform. ↩︎This is one of the reasons I have been bullish on pure dart bindings, which should’ve been obvious in the hindsight. ↩︎

I believe these are more illustrative than calling an integer / double function. These examples already involved solving the class loader problem and figuring out a way to get application context on Android. ↩︎

Actually it can, if you pass

-parametersto the compiler. But it’s very inconvenient to recompile a binary library. ↩︎We are considering parsing Kotlin sources through a documentation engine such as Dokka, or even parsing the JavaDoc directly. ↩︎

It’s certainly possible to bind to standard library classes. In this standalone example however, we couldn’t do this without adding a system-dependent path to config. in_app_java example in jnigen repo shows an example without much extra configuration. With some circus around module layout, it’s also possible to use Android SDK 28 sources, which are well-formed. Here’s an example. ↩︎

An observant reader will see that Bouncy Castle dependencies are specified explicitly. These aren’t hard dependencies of PDFBox but required transitively by most of the Java code we parse. ↩︎